|

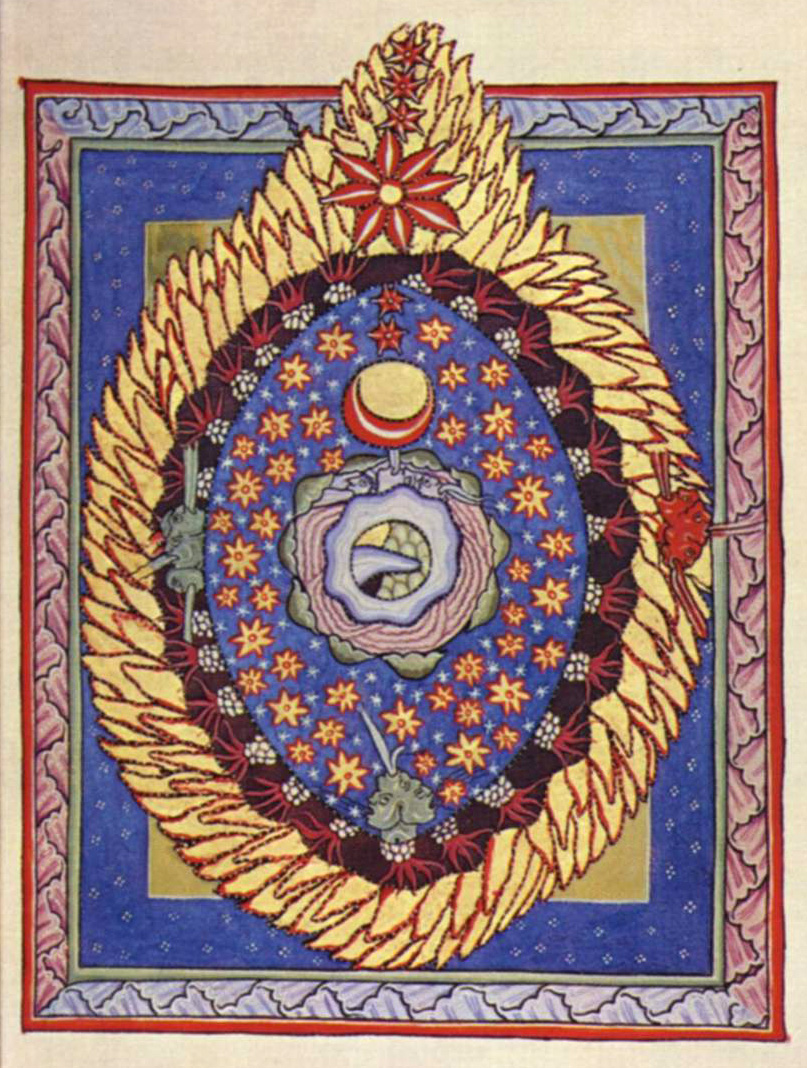

| Abraham, Sarah and Hagar Foster Bible 1897 Source: wikicommons |

This week the responsories take us through the stories of Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 12 - 26); the Scriptural reading sequence, though, stops on Tuesday at Genesis 14, and doesn't resume again until the Second Sunday of Lent, at Genesis 27.

The weekday Patristic readings

The use of Patristic readings at Matins of three readings instead of Scriptural ones is standard in the modern office for higher class days such as Ash Wednesday.

The use of Patristic sermons on the Gospel of the day instead of Scriptural texts on Lent weekdays, though, was a tenth century innovation that gradually spread, and was eventually entrenched in the post-Tridentine breviaries.

Oddly though, new responsories were not composed to match the change: instead they mostly continue to reflect the (previous) Scriptural reading sequence from Genesis, this week focusing on the stories of Abraham and Isaac.

A case for returning to the older tradition?

The use of Patristic sermons on Lent weekdays was, perhaps, a logical extension of the continuing clericalisation of the Office, including the addition of collects from the Mass of the day, and the eighth or ninth century move to replace the reading of the New Testament specified by the Rule for the Third Nocturn of Sundays, with Patristic readings on the Sunday Gospel.

But the daily reading of at least Genesis to Exodus in the pre/Lent period seems ancient and near universal at least in the West: St Ambrose's commentaries on Genesis used in the second Nocturn, on Noah, Abraham, Jacob and Joseph are all products of his regime of daily sermons during Lent; and Caesarius of Arles (more or less contemporary to St Benedict) also left a series of sermons on Genesis for use in this period.

The change to the Office did not, of course, necessarily mean abandonment of the traditional reading cycle: in a monastery, the Scriptural sequence could, at least in theory, be maintained through lectio divina, refectory, and evening readings (though the evidence on whether it actually was maintained this way in places where the Patristic reading were inserted is ambiguous). The retention of the Genesis 'historia' responsories might perhaps have been regarded as a way of assisting the assimilation of this material even though it was mostly being read outside the Office.

The responsories

Several of the responsories for this week (Sunday no 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9) actually relate more to the readings that would presumably have occurred next week, so I will discuss them in that context.

Instead let me provide you with the texts of some of the responsories most relevant to this week for your consideration.

They highlight Abraham's obedience, and the various promises made to Abraham.

The first tells of his call to leave all and follow the instructions of God:

Sunday no 1: Genesis 12:1-2

℟. Locútus est

/ Dóminus ad Abram, dicens: † Egrédere de terra tua, et de cognatióne tua, et

veni in terram quam monstrávero tibi: * Et fáciam te in gentem magnam.

℣. Benedícens

benedícam tibi, et magnificábo nomen tuum, † erísque benedíctus.

|

℟. The Lord

spake unto Abram, saying: Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred,

and go unto the land that I will show thee, * And I will make of thee a great

nation.

℣. I will

surely bless thee and make thy name great, and thou shalt be blessed.

|

The second highlights his priestly role, paralleling a responsory on the same subject in relation to Noah (Gen 8, resp 5 of Sexagesima):

Monday no 1: Genesis 13:8

℟. Movens / Abram

tabernáculum suum, venit et habitávit iuxta convállem Mambre: * Ædificavítque

ibi altáre Dómino.

℣. Dixit autem Dóminus ad eum: Leva óculos tuos,

et vide: † omnem terram, quam cónspicis tibi dabo, et sémini tuo in

sempitérnum.

|

℟. Abram

removed his tent, and came, and dwelt by the vale of Mamre * And built there

an altar unto the Lord.

℣. And the

Lord said unto him Lift up thine eyes, and look; all the land which thou

seest, to thee will I give it, and to thy seed for ever.

|

Curiously, none of the responsories highlight the important story of Melchisedech, chronicled in Genesis 14, though a responsory on this chapter is used on the (much later) feast of Corpus Christi.

Chapter 15 deals with a vision of Abraham, and God's promise to him of descendants and land:

Wednesday no 2 (Sunday no 10): Genesis 15:1

℟. Factus est / sermo Dómini

ad Abram, dicens: * Noli timére, Abram: † ego protéctor tuus sum, et merces

tua magna nimis.

℣. Ego enim sum Dóminus Deus

tuus, † qui edúxi te de Ur Chaldæórum.

|

℟. The word of

the Lord came unto Abram, saying * Fear not, Abram I am thy shield, and thy

exceeding great reward.

℣. For I am

the Lord thy God That brought thee out of Ur of the Chaldees.

|

Chapter 16 deals with the birth of Ismael; chapter 17, the covenant sealed by circumcision, and Isaac.

Sunday no 4 [Friday, Saturday] Genesis 17:19, 18:10

Sunday no 4 [Friday, Saturday] Genesis 17:19, 18:10

℟. Dixit /

Dóminus ad Abram: † Sara uxor tua páriet tibi fílium * Et vocábis nomen eius

Isaac.

℣. Revértens

véniam ad te témpore isto, vita cómite, † et habébit fílium Sara uxor tua.

|

℟. And God

said to Abraham: Sara thy wife shall bear thee a son, * And thou shalt call

his name Isaac.

℣. I will

return and come to thee at this time, life accompanying, and Sara thy wife

shall have a son

|

The natural flow of the reading sequence suggests that chapter 18, which deals with the visit of the three angels, could be read on Saturday.

The final Abraham responsory set for Sunday (no 11) actually comes from James 2:23, and provies a nice overall summary of Abraham's importance. The Cantus database listing comes from various thirteenth and fourteenth century British manuscripts, for the Sarum rite, but Dominique Crochu has noted that it is also attested to for Italy in various Beneventan and Franciscan manuscripts:

℟. Crédidit / Abram Deo, et reputátum est ei ad

iustítiam: * Et ideo amícus Dei factus est.

℣. Fuit autem iustus coram Dómino, et ambulávit in

viis eius.

|

℟. Abraham

believed God, and it was counted unto him for righteousness. * And therefore

he became the friend of God.

℣. For he was

righteous in the sight of the Lord, and walked in His ways.

|

The readings

Quinquagesima Sunday: Genesis 12: 1-19

Monday after Quinquagesima Sunday: Genesis 13:1-16

Tuesday: Genesis 14: 8-20

Wednesday: Homily of St Augustine - Our Lord on the Mountain, Bk II ch 12 [Genesis 15]

Thursday: St Augustine On the Harmony of the Gospels, Book II ch 20 [Genesis 16]

Friday: Homily of St Jerome - On Matthew 5:44-45; 6:1 [Genesis 17]

Saturday: Homily of St Bede - On Mark 2:6 [Genesis 18: 1-15]