|

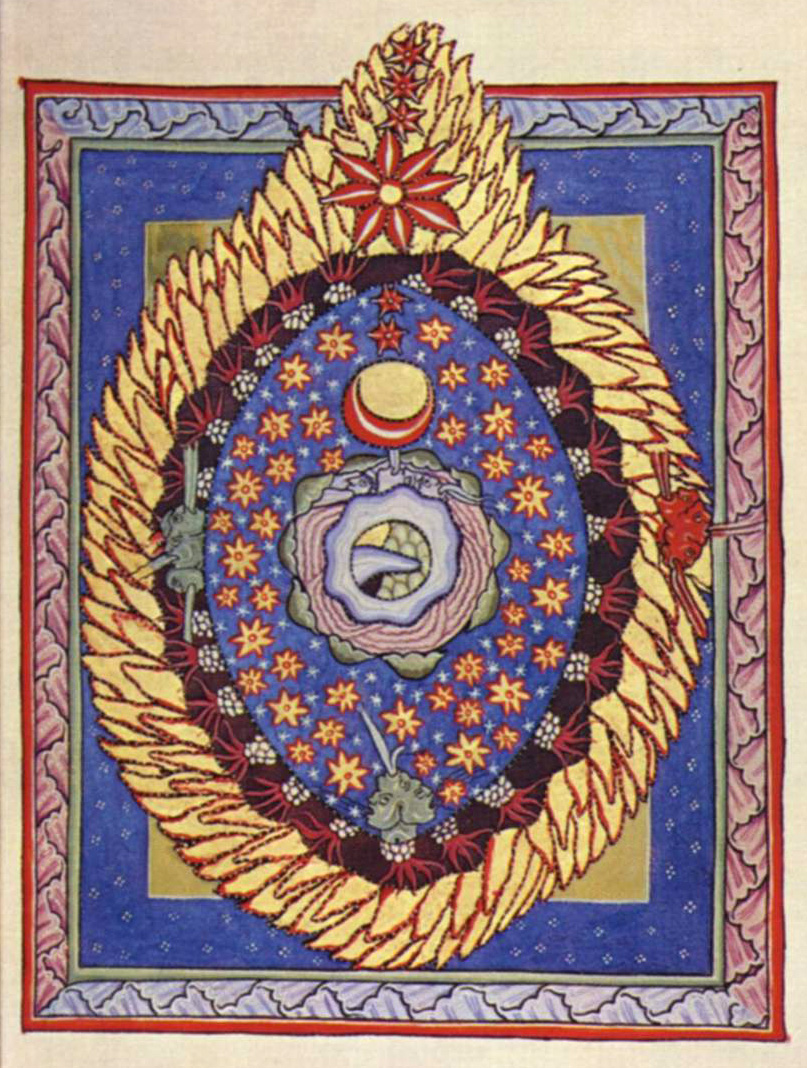

| Scivias, Hildegarde von Bingen Image source: wikipedia |

This Sunday marks the start of a new liturgical season, the pre-Lenten season of Septuagesima, which is also effectively the starting point of the Matins reading cycle, with the reading of Genesis.

This year, I thought I would try and provide a few notes on the Matins reading cycle, including its history and inner logic, and on the associated responsories.

Overview of the reading cycle

The existence of a Matins reading cycle in use in Rome can be traced back to at least the sixth century, and it shares many of the same features as that which survives to this day (in the 1962 Office at least). The particular arrangement of the Biblical books we use know though, reflects some tweaks made to the cycle, perhaps in the eighth century.[1]

And those 'tweaks' were, I think, designed to give it an inner logic based around two key poles, our Redemption through the the Passion and Resurrection; and the Incarnation and above all showing forth of God in the Epiphany.

The cycle arguably starts, in my view, during Septuagesima and Lent, with preparation for our redemption, for in this period we trace the story of the world from creation, the fall, and the promises made to the Old Testament patriarchs.

During Passiontide the Lamentations of Jeremiah typologically foreshadow the events of Holy Week.

From Easter we read the story of the Church after the Crucifixion, in Acts, the Catholic Epistles and above all Apocalypse which also foreshadows that which is still to come.

After Pentecost, we read the history of the Davidic kingdom, which is a type of the church established by Christ, with its reminders of the travails it will always face in this world.

We then turn to the instructional books, which teach us how to live up to and attain the kingdom, to stay faithful, in the form of the Wisdom literature; and those that provide us with examples to emulate, such as Job, Judith, Esther and Maccabees.

The cycle then turns to preparation for the various epiphanies, including the birth of Christ, in the readings of the Prophets in November and December.

And the cycle ends, it seems to me, with the epistles of St Paul, the doctor to the Gentiles, as a fitting accompaniment to a season in which we celebrate God being made visible to all nations, and are instructed in the mission to convert them.

The season of Septuagesima

In St Benedict's Rule, Septuagesima is not mentioned - instead the key feature of the season, suppression of the Alleluia, started with Lent (RB 15).

In this St Benedict seems not to have been following the Roman pattern of his day, since Quinquagesima at least is attested to for Rome for the first half of the sixth century [2], and Septuagesima itself was probably a creation of St Gregory the Great.

The pre-Lent season, though, was gradually introduced in Rome and elsewhere, and by around c625 the Pope of the day, Honorius had to order 'that the monks should leave off the Alleluia in Septuagesima' (see the Liber Pontificalis).

One of the aims of the new season may have been to allow the reading of the first seven books of the Bible, traditionally assigned to Lent, to be given more time. If so, however, this benefit was relatively short-lived!

Genesis to Judges?

The reading of the first books of the Bible during Lent, and then the last books of the Bible (Catholic Epistles an Revelation) during Eastertide seems to have been a fairly ancient pattern, but it is one that has been gradually eroded.

The oldest surviving lectionary for Rome, Ordo XIV, which probably dates from the first half of the seventh century but describes sixth century practices, specified that from the week before Lent up to the week before Easter, the first seven books of the Bible should be read, that is, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua and Judges.

By the early ninth century though, Amalarius of Metz (in his Liber de ordine Antiphonarii) attests that Septuagesima Sunday itself was devoted to an elaborate ceremony of burying the alleluia (abolished in the elventh century), and the responsories of the day were festooned with them. Instead the reading of Genesis started the following Sunday, Sexagesima.

Not all Roman basilicas may have followed this pattern, however, and Ordo XIII, for example, which may date from around the same time period, started the Genesis responsories on Septuagesima as we do today.

Either way, the surviving sets of responsories to accompany the period up to Holy Week, which probably date from the eighth century reorganisation of the psalter attested to in Ordo XIII [3], suggest a much more limited reading pattern, since they relate only to Genesis and Exodus, covering Adam, Noah, Abraham, Jacob, Joseph and Moses.

And in the tenth century, the Scriptural readings for Lent started to be replaced, in many places, by Patristic readings on the Gospel of the day, a pattern adopted in the post-Tridentine Roman and Benedictine Offices. But we will come back to this in due course!

The readings and responsories for Septuagesima week

In the 1962 Benedictine Office (and it predecessor breviaries) the Scriptural readings this week are from Genesis 1 - 5:

Septuagesima Sunday: Genesis 1:1-26

Monday after Septuagesima Sunday: Genesis 1:27-31; 2: 1-10

Tuesday: Genesis 2:1-24

Wednesday: Genesis 3:1-20

Thursday: Genesis 4:1-16

Friday: Genesis 4:17-26; 5:1-5

Saturday: Genesis 5:15-31

The responsories cover the same ground, and seek to draw our particular attention to four key events:

- the seven days of creation (responsories 2&4);

- the creation of man and woman (responsories 1, 3, 6 &7);

- the story of Adam and the Fall (responsories 5, 8, 9, 10, 12 & responsory 1 of Monday); and

- the murder of Abel (responsory 11).

Notes

[1] The eighth century date was convincingly proposed by Brad Maiani, in Readings and Responsories: The Eighth-Century Night Office Lectionary and the Responsoria Prolixa, The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring, 1998), pp. 254-282. the key changes were to cut back the time allocated to Kings and Chronicles; consolidate the reading of the prophets to November and December; and introduce the reading of the Pauline Epistles during Epiphanytide.

[2] The edition of the Liber Pontificalis written in the sixth century mentions it in relation to Popes Telesphorus and Vigilius.

[3] See Maiani, op cit, as well as Constant J. Mews (2011) Gregory the Great, the Rule of Benedict and Roman liturgy: the evolution of a legend, Journal of Medieval History, 37:2, 125-144; and Thomas Forrest Kelly, Old-Roman Chant and the Responsories of Noah: New Evidence from Sutri, Early Music History, Vol. 26 (2007), pp. 91-120.

No comments:

Post a Comment